At least 8,000 tigers are estimated to be held across more than 200 tiger farms in East and Southeast Asia. That’s more than double the number of tigers left in the wild. Tiger farms are facilities that breed tigers for commercial sale or trade of tiger parts. Most of the captive tigers are located in China, with the remaining animals spread almost exclusively between Thailand Lao PDR; and Vietnam.

WWF believes the current crisis of captive breeding operations within tiger farms is a threat to wild tiger populations in two significant ways:

- The movement (or leakage) of tiger products from tiger farms to consumer markets complicates and thus undermines enforcement efforts aimed at identifying and stopping the trade in wild tiger products.

- Tiger

farms help perpetuate (and grow) demand by legitimizing or normalizing

the demand for tiger parts in a region currently experiencing profound

and sustained growth of consumer classes. Even a modest increase in the

demand for tiger products could trigger immense poaching pressures on

wild populations.

Leigh Henry, WWF’s Director of Wildlife Policy, recently returned from a trip to China – the country where tiger farms started back in the 1980s. Leigh and her colleagues visited one of the world’s largest tiger farms– the Harbin Siberian Tiger Park – in the northeast corner of China. Here’s what Leigh saw on her visit:

We first boarded a bus covered in protective bars that drove us through wide-open enclosures where some of the tigers are housed. The tour guide stated that they house about 700 tigers there, as well as around 600 in offsite facilities. They feed the tigers about 70-80 kilos of meat per day, at a cost of about $140 per tiger. Given the minimal crowds at the park, even on a weekend, one is left to wonder how such a facility can possibly be profitable.

Visitors on the bus were given the option to pay to feed the tigers. A couple of people on our bus chose to do so and fed them raw meat out of a slot in the window. There was also meat and live chickens available for feeding as we continued to walk through other parts of the Tiger Park after the bus tour.

There were tigers in the wide-open enclosures, in some smaller ones, as well as in 51 concrete-floored kennels (1-3 tigers in each). We could hear more tigers that weren’t on display to the public. The tigers we were able to see appeared to be in good health, but given we didn’t have access to them all, we can’t speak to the condition of all of the animals held in the Park.

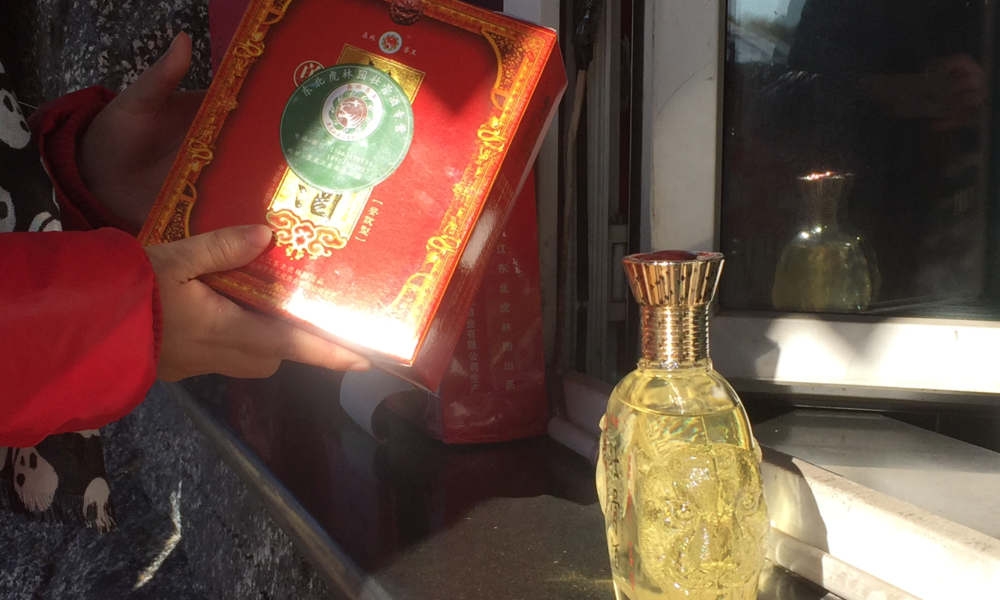

As we exited the park, the shops that had been closed when we entered were now open. There was one openly displaying and selling “special bone wine” and wine containing Panthera leo (lion). There were only a handful of lions at the Tiger Park (compared to the hundreds of tigers…), which begs the question as to the actual contents of the bottle. Sale of tiger products, or any products labeled as containing tiger, is banned in China, as well as in international trade. Perhaps upon our exit, we had answered our question as to how such a facility could turn a profit…

Given the illegal activities and conservation problems attributed to Asia’s tiger farms, WWF is working to ensure government commitment to phasing out these farms and banning commercial trade in all tiger parts and products, from any source.

I have the daunting task of leading this body of work for the WWF network and, as such, will be traveling to three more countries where we’re focusing our work, Vietnam, Thailand and Laos, to work more closely with our offices on the ground, and with key government and NGO partners. WWF will not win this fight alone.

Enviroshop is maintained by dedicated NetSys Interactive Inc. owners & employees who generously contribute their time to maintenance & editing, web design, custom programming, & website hosting for Enviroshop.