Delta systems such as coastal Louisiana are beautiful and unique intersections of communities, ecosystems and industry. But the wide variety of interests in these areas can also lead to discord as we plan for the future of our often-vulnerable coastal regions.

As complex restoration projects are implemented, how do we balance the needs of the ecosystem and communities? How do we reduce negative impacts to fisheries and industry, and make sure certain wildlife won’t benefit at the expense of others?

A diverse, interdisciplinary group of 12 scientists with decades of on-the-ground research in Louisiana recently tried to work past conflicting interests to tackle challenges left by decades of mismanagement of the region’s vital wetlands.

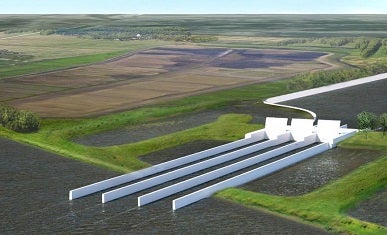

Their task: to figure out how so-called sediment diversions affect different aspects of the environment, and how to operate them to build land while providing the greatest good.

The report they released in July 2016 was significant because it was the first attempt to look holistically at how best to operate these engineered structures that release Mississippi River sediment and freshwater into the wetlands.

Most important, it was the first time this kind of conversation took place with a group of diverse viewpoints, some of whom were sought out because they questioned the benefits of sediment diversions. And yet, they were able to hammer out recommendations for Louisiana’s coastal restoration, the largest environmental restoration effort of our time.

Restoration comes at a cost

The Sediment Diversion Operations Expert Working Group’s report came as the state of Louisiana prepares for a major project south of New Orleans, set to break ground in 2020.

After nearly a century of the Mississippi River being completely dislocated from its wetlands by levees and after decades of planning, we are nearing a point where a man-made project will mimic this historic natural process and deliver sediment and water to the coastal wetlands that are sinking without it.

But sediment diversions also come at a cost.

When river water and sediment is diverted into nearby basins, it changes many aspects of the environment – hydrology, water quality, vegetation, fish and wildlife as well as communities and local industry.

So during eight full-day meetings, which I facilitated, the working group, and an additional 42 guest experts, discussed how the operation of a sediment diversion could affect every single interest of the coast.

A different way to ask questions

We looked at each individually and asked questions such as, “If land building was our one and only goal without any other constraints, how would we operate a sediment diversion?”

Or, “What if healthy marsh vegetation was our one and only goal?” “What about oysters? Or Brown shrimp?” “What about flood risk to coastal communities?”

This approach helped us identify an optimal strategy for each interest, to evaluate commonalities and discrepancies across various operations strategies, and – finally – to reach consensus.

It has changed the conversations with affected and often disenfranchised coastal communities.

The final report laid out recommendations that describe when and how to operate a diversion both initially and over time, as well as how to work with industry, fishermen and local communities.

We were not prepared for the immense and positive feedback we received. The report has changed the conversation Environmental Defense Fund and our partners have with affected and often disenfranchised coastal communities.

“We’ve been waiting to have this conversation”

Fishermen, who had long been publicly opposed to diversions, told me, “This is what will bring us to the table.”

Local government officials who had passed resolutions against diversions said, “We’ve been waiting to have this conversation.” Even the chairman of the Louisiana Oyster Task Force, an industry with long-standing concerns about the approach, thanked us for bringing the group together.

Of course, Louisiana is not unique. Coastal regions in other parts of the country, or the world, wrestle with similar complex challenges.

What we learned about bringing all the diverse and often conflicting interests to the table could be applied to other places that face similar risks of coastal erosion, rising seas and increased storms in our warming climate. It shows what can be accomplished when we begin to really talk.

Natalie Peyronnin is the director of science policy for EDF’s Mississippi River Delta Restoration program and the convener of the Sediment Diversion Operations Expert Working Group. She works to ensure sound science is being utilized to plan, design, implement and adaptively manage projects and policies, with a focus on system dynamics. Natalie was a Senior Scientist for Louisiana’s Coastal Protection and Restoration Authority, where she served as the technical lead and science communicator for the 2012 Coastal Master Plan. Natalie also worked as Science Director for the Coalition to Restore Coastal Louisiana. Natalie has a B.S. in Wildlife and Fisheries Management, with minors in Forestry and Zoology & Physiology from Louisiana State University, as well as an M.S. in Oceanography and Coastal Sciences from Louisiana State University.

By Natalie Peyronnin, Director of Science Policy, Mississippi River Delta Restoration, Environmental Defense Fund

This blog originally appeared on EDF Voices.

Enviroshop is maintained by dedicated NetSys Interactive Inc. owners & employees who generously contribute their time to maintenance & editing, web design, custom programming, & website hosting for Enviroshop.