California’s landscape will transform in a changing climate. While extended drought and recent wildfires seasons have sparked conversations about acute impacts today, the promise of changes to come is no less worrying. Among the challenges for water management:

- The Sierra Nevada mountain range – an important source of water storage for the entire state – is expected to see a 60% reduction in total snowpack by the end of the century, along with earlier melting times.

- Average July temperatures in California’s Central Valley – an indispensable agricultural region – are expected to rise by up to 3.9 °F by 2050, reducing yields for many crops and stressing irrigation demand.

- Precipitation is expected to become less predictable throughout the state.

These changes will make water resources less reliable when they are needed most, rendering water storage an even more important feature of the state’s water system.

One promising option for new storage makes use of groundwater aquifers, which enable water users to smooth water consumption across time – saving in wet times and extracting during drought. However, when extraction exceeds recharge over the long term, “overdraft” occurs. Falling water tables increase pumping costs, reduce stored water available for future use, and entail a host of other collateral impacts. Historically, California’s basins have experienced substantial overdraft.

Falling water tables reflect inadequate institutional rules

One cause of the drawdown is California’s history of open-access management. Any landowner overlying an aquifer can pump water, encouraging a race to extract. Enclosing the groundwater commons and thereby constraining the total amount of pumping from each aquifer is critical for achieving efficient use and providing the volume and reliability of water storage that California will need in the future. However, despite evidence of substantial long-run economic gain from addressing the problem, only a few groups of users in California have successfully adopted pumping regulations that enclose the groundwater commons.

SMGA addresses overdraft—but pumpers must agree to terms

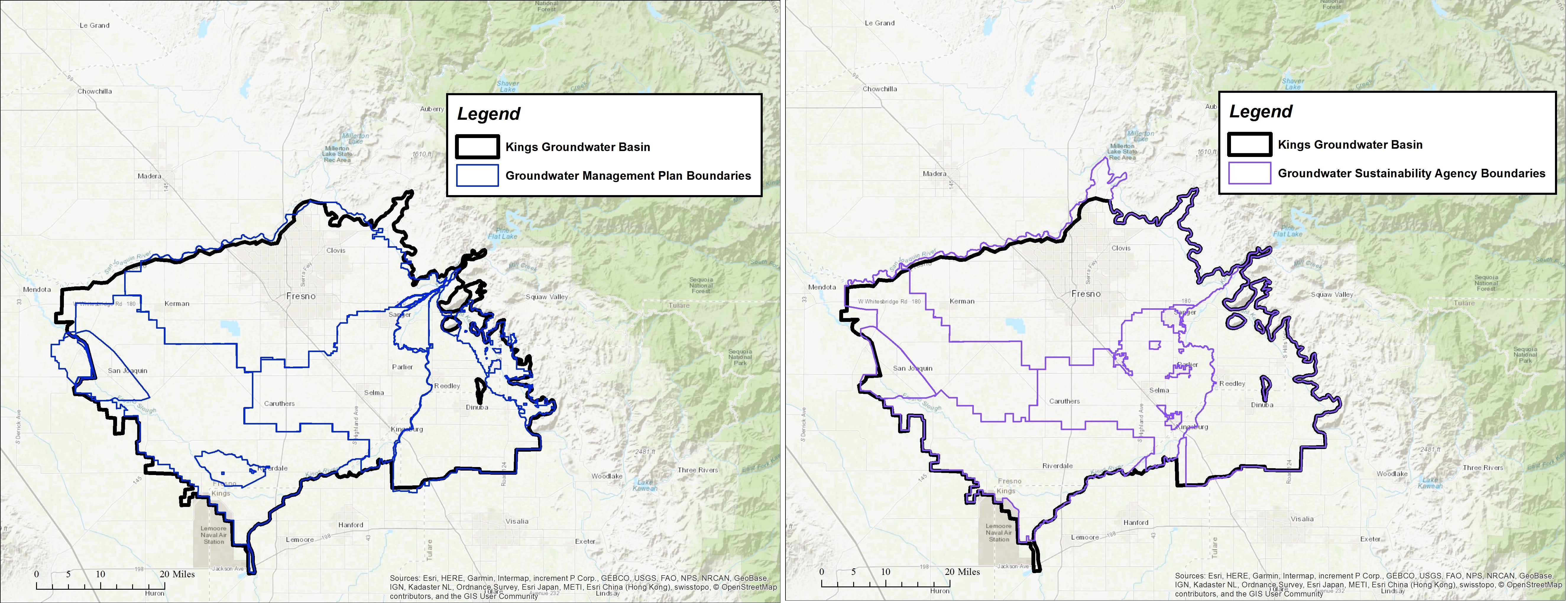

California’s Sustainable Groundwater Management Act (SGMA) of 2014 aims to solve this challenge by requiring stakeholders in overdrafted basins to form Groundwater Sustainability Agencies (GSAs) and create plans for sustainable management. However, past negotiations have been contentious, and old disagreements over how best to allocate the right to pump linger. The map presented below illustrates how fragmentation in (historical) Groundwater Management Plans also tracks with current fragmentation in Groundwater Sustainability Agencies (GSAs) under SGMA. Such persistent fragmentation suggests fundamental bargaining difficulties remain.

Spatial boundaries of self-selected management units within basins under SGMA (GSAs) mirror those of previous management plans (GMPs). Persistent fragmentation may signal that adoption of SGMA doesn’t mean the fundamental bargaining difficulties facing the basin users have disappeared.

New research, co-authored with Eric Edwards (NC State) and Gary Libecap (UC, Santa Barbara) and published in the Journal of Environmental Economics and Management, provides broad insights into where breakdowns occur and which factors determine whether collective action to constrain pumping is successful. From it, we’ve gleaned four suggestions for easing SGMA implementation.

Understanding the costs of contracting to restrict access

To understand why resource users often fail in adopting new management institutional rules, it’s important to consider the individual economic incentives of various pumpers. Even when they broadly agree that groundwater extraction is too high, collective action often stalls when users disagree about how to limit it. When some pumpers stand to lose economically from restricting water use, they will fight change, creating obstacles to addressing over-extraction. When arranging side payments or other institutional concessions is difficult, these obstacles increase the economic costs of negotiating agreement, termed “contracting costs.”

To better understand the sources of these costs in the context of groundwater, we compare basins that have adopted effective institutions in the past with otherwise similar basins where institutions are fragmented or missing. Even when controlling for the level of benefits, we found that failures of collective action are linked to the size of the basin and its user group, as well as variability in water use type and the spatial distribution of recharge. When pumpers vary in their water valuation and placement over the aquifer, the high costs of negotiating agreement inhibit successful adoption of management institutions, and overdraft persists. Indeed, in many of California’s successfully managed basins, consensus did not emerge until much farmland was urbanized, resulting in a homogenization of user demand on the resource.

Four key takeaways to ease agreement

In the face of such difficult public choices, how can pumpers and regulators come to agreement? Four main recommendations result from our research:

- Define and allocate rights in a way that compensates users who face large losses from cutbacks in pumping. Tradable pumping rights can help overcome opposition. Pumpers can sell unused rights and are oftentimes made better off. The option to sell also incentivizes efficient water use.

- Facilitate communication to reduce costs of monitoring and negotiations. The Department of Water Resources has already initiated a program to provide professional facilitation services to GSAs.

- Promote and accept tailored management. Stakeholders and regulators should remain open to approaches that reduce contracting costs by addressing issues without defining allocations or attempting to adopt the most restrictive rules uniformly throughout the basin. For example, pumpers have successfully adopted spatially restricted management rules to address overdraft that leads to localized problems; others have adopted well-spacing restrictions that reduce well interference without limiting withdrawals.

- Encourage exchange of other water sources. Imported, non-native surface water may lower contracting costs because it can save users from large, costly cutbacks. Pumpers have written contracts to share imported water in order to avoid bargaining over a smaller total pie; where such water is available, exchange pools (such as those described here) can help to limit the costs of adjustment.

SMGA is a large-scale public experiment in collective action. To avoid the failures of previous attempts to manage groundwater, stakeholders crafting strategies for compliance and regulators assessing them should keep in mind the difficult economic bargaining problem pumpers face. Hopes for effective, efficient, and sustainable water management in California depend on it.

Enviroshop is maintained by dedicated NetSys Interactive Inc. owners & employees who generously contribute their time to maintenance & editing, web design, custom programming, & website hosting for Enviroshop.